One of the highlights of this year’s American Academy of Religion annual meeting was a NAASR panel responding to On Teaching Religion.  The book, edited by Christopher Lehrich, is a collection of J.Z. Smith’s essays on teaching. Until this volume, many of the essays were out of print and hard to find. Lehrich chose not to include many of the most commonly cited and widely available essays, focusing instead on providing examples of Smith’s work with which even his frequent readers may be unfamiliar. Having already browsed the volume, I’m excited about the role it can play in encouraging discussion about how, why, and what we teach.

The book, edited by Christopher Lehrich, is a collection of J.Z. Smith’s essays on teaching. Until this volume, many of the essays were out of print and hard to find. Lehrich chose not to include many of the most commonly cited and widely available essays, focusing instead on providing examples of Smith’s work with which even his frequent readers may be unfamiliar. Having already browsed the volume, I’m excited about the role it can play in encouraging discussion about how, why, and what we teach.

Continue reading

Tag: J.Z. Smith

There’s a lot to say about the coverage of Reza Aslan’s interview with Fox News.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YY92TV4_Wc0

Andrew Kaczynski over at Buzzfeed covered the interview under the title “Is This The Most Embarrassing Interview Fox News Has Ever Done?” (I bet you can’t guess how he answers that particular question.) Amusement and outrage was evident on Twitter as well, where the #foxnewslitcrit hashtag has become popular in religious studies circles.

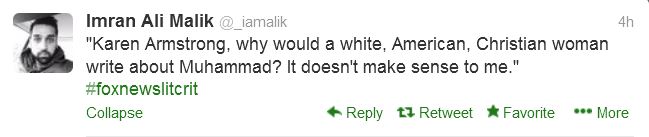

The most interesting part of this, to me, is Fox News host Lauren Green’s opening question: “You’re a Muslim, so why did you write a book about the founder of Christianity?” The logic of Green’s question seems to be that being a Muslim precludes one from studying Christianity. At the very least, it seeks to color with suspicion those Muslims who choose to study it. There’s much to be said about this, of course, and one of my colleagues Thomas Whitley already summed up much of what I’d like to say. So, too, did Imran Ali Malik:

This post originally appeared on the Bulletin for the Study of Religion’s blog. You can view the rest of the responses as they are posted on the Bulletin’s blog.

**

“When we conceal from our students our hard work, that which is actually the way we earn our bread and butter, we produce a number of consequences. I remember testifying once before the California state legislature and facing a legislator who wanted to know why professors should be paid to read novels, when the legislator himself read novels on the train every day. Well, that was the price of our disguising the work that goes into things.”

-J.Z. Smith, “Duplicity in the Disciplines”

“A new present requires a new past.”

– Sydney Ahlstrom (1972)

In “Evidentiary Boundaries and Improper Interventions,” Baker argues that our field suffers from a lack of attention to the boundaries which separate legitimate from illegitimate evidence. She puts it most succinctly in the footnotes: “What I want to point to, however, is how some evidence is employed to mark legitimate religion/religions” (Baker 2012, 10). Baker’s attentiveness to these boundaries is helpful, as are her suggested improvements. Baker argues that it cannot be improved by simply adding more to the canon. Expanding coverage to every group for the sake of doing so, she suggests, smacks of an outmoded trust in pluralism as progress. However, since I suspect a post detailing my agreement with Baker’s article would not make for an interesting read, I will highlight a few areas to challenge. In short, though I agree with the substance of Baker’s critique, it is with the why of the critique that I am more troubled.

Baker’s evidentiary concerns are evidence of astute scholarly analysis: “If the “illegitimate” functions as code for “inauthentically” religious, we should push against that boundary to know why exactly legitimacy or illegitimacy still matters for the subfield” (Baker 2012, 7, emphasis my own). While Baker’s observations are insightful, her normative claims about the state of the field and its potential future—that which “we should push against—warrant further analysis. Authenticity struggles matter to Baker because “authentic” religion still matters for American culture as a whole. Yet whether it is to achieve tax-exempt status (Urban 2011) or to secure political representation (Flake 2003) the boundaries of legitimate/illegitimate are not just those drawn (or imagined) by scholars. The fear that Baker identifies and hopes to alleviate, then, is unavoidable because the category of religion is contested in the broader public sphere. Continue reading