A version of this post originally appeared on the blog for the Bulletin of the Study of Religion.

**

In the course of preparing a new project on the Vietnam War, I stumbled upon a series of news articles covering Vietnamese President Sang’s visit to the United States last month. After meeting with President Obama at the White House, the two leaders held a press conference to recap their discussion. In one of the countless minor controversies that seem to comprise daily life in Washington, D.C., some of President Obama’s political opponents were critical of his closing remarks in which he said the following:

At the conclusion of the meeting, President Sang shared with me a copy of a letter sent by Ho Chi Minh to Harry Truman. And we discussed the fact that Ho Chi Minh was actually inspired by the U.S. Declaration of Independence and Constitution, and the words of Thomas Jefferson. Ho Chi Minh talks about his interest in cooperation with the United States. And President Sang indicated that even if it’s 67 years later, it’s good that we’re still making progress.

The reaction by some on the American right was swift. In an article entitled “Uh Ho,” Fox News reported on the incident: “It may come as some unwelcome news to the families of the nearly 60,000 Americans who died in the Vietnam War that the whole thing was just a misunderstanding.” The debate was lively on Twitter, with (prominent?) conservative Allen West chiming in:

West’s post is representative of those who were outraged that Obama would compare Ho Chi Minh to the Founding Fathers (even if it was only Jefferson).

While I found the general revulsion to Ho Chi Minh unsurprising, I was struck by how many people were insulted by the notion that Ho could even be inspired by Jefferson. Fox’s Chris Stirewalt wrote that, “In Obama’s credulous citing of the Constitution as an inspiration, there is particular historical dissonance. One of the great murders of the 20th century could not have been truly inspired by the most significant advancement of the rights of the individual in human history.”

Historical dissonance, mind you. The latest kerfuffle presents a reminder of the ways in which specific readings of texts authorize particular historical narratives. Teleological arguments regarding the course of American history aside (fish, barrel, etc.), this case is a good example of how the American founders’ words are taken to have very specific (and limited) meanings by some of their readers. I’m reminded of Bruce Lincoln’s “How to Read a Religious Text” (2006), in which Lincoln argues that one of the primary markers of a religious text is that “characteristically, they connect themselves—either explicitly or in some indirect fashion—to a sphere and a knowledge of transcendent or metaphysical nature, which they purportedly mediate to mortal beings through processes like revelation, inspiration, and unbroken primordial tradition” (127). Considering the strategic choices made when classifying the Founders as (a)/religious are nothing new (cue the late Robert Bellah), but this story serves as a good reminder of the way in which people writing about the Founders often engage in rhetorical practices quite familiar to scholars in the academic study of religion.

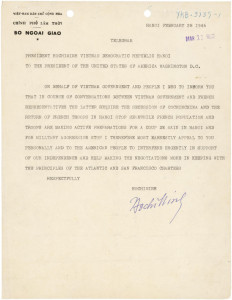

This approach also renders the story useful in the classroom, since it provides a contemporary example of the tricky business of policing categorical distinctions. In this case, Ho is a “dictator,” and dictators and the Declaration of Independence don’t mix. Faded from view, of course, is Ho’s unanswered letter to President Truman requesting aid in ending French colonial rule as is President Eisenhower’s decision to suspend the elections in which Ho planned to run for office.

People read texts differently. News stories like this one can be a useful way to not only remind students that texts lack intrinsic meaning but that our attention is best spent on investigating the act of assigning meaning. In this particular story, Jefferson’s words mean something to those who were outraged, and that something can be determined neatly and precisely. Furthermore, the text of the Declaration of Independence not only means something specific but, if interpreted correctly, can inspire only a limited set of actions in keeping with that meaning. So though Ho Chi Minh certainly read Jefferson, the argument goes, he must not have understood Jefferson since Ho did things which are un-American (apparently unlike things which Jefferson did and are apparently quintessentially American–such as, say, slavery). Thus Obama linking Jefferson to Ho Chi Minh is particularly troubling, since it suggests either that President Obama (a) does not understand Jefferson or, worse, (b) he understands Jefferson but wishes to salvage Ho Chi Minh’s historical record by rinsing it liberally with the image of the Founders.

Option (b) fits within the interpretive logic of many who see President Obama as essentially un-American (and therefore socialist/ communist/ fascist/ Islamo-fascist). Thus we have the artwork of flickr user “Templar1307” depicting Obama in the place of Lenin, facetiously used in coverage of the event by Mother Jones. Cue Lincoln: “Those whose consciousness has been shaped by such a vision are conditioned to see, accept, ponder, and admire the same “cosmic” order in all its (putative) instantiations…Moreover, they experience that order as one more confirmation of the pattern they have learned to identify with the nature of the cosmos, for all that it is the product of their own discourse and practice.” (139, my emphasis).

Leave a Reply